When it comes to cartridges and bullets, one of the most argued topics in the previous decades was .45ACP vs 9mm Luger (aka 9×19). Traditionalists argued that the .45ACP with a heavier 230gr bullet moving at a relatively slow ~830 feet per second made for better stopping power than the 9×19’s lighter 115gr / 124gr bullet moving at ~1200 fps.

Do you pick a slow and heavy bullet or the fast and light for handgun use? Stopping power (energy) or more rounds in the magazine?

This debate has lessened in recent years as bullet technology has advanced and schools of thought have changed. But advancements in bullet designs have also brought up this debate, albeit in a different context, within the realm of precision rifle and long range shooting.

For a long time, the .308 Winchester was the defacto cartridge for precision rifle and long range shooting. The 30cal 168gr BTHP (e.g. Sierra Match King) was the bullet most people shot. Then the military and other shooters realized that the venerable 168gr was not consistent at 1000 yards due to insufficient ballistic coefficient (BC). The bullet simply could not cut through the air and maintain stable supersonic flight to 1000 yards with regularity.

Ballistic coefficient is a fundamental concept in precision shooting. To get a decent understanding of BC, you are highly encouraged to read Applied Ballistics for Long Range Shooting by Bryan Litz. This has become critical reading for all shooters who want an understanding of ballistics as it applies to precision and accuracy.

A 175gr BTHP was created with a resulting increased BC over the 168gr BTHP, whereby it could maintain stable supersonic flight to and just over 1000 yards on a consistent basis, even though it had a slower muzzle velocity than the 168gr in the .308 Winchester cartridge. The simple fact is that the heavier bullet lost velocity at a slower rate.

In the early 2000’s as people began adopting cartridges other than .308 Winchester for precision and/or long range use, people tended to favor the highest BC bullet available and usable in the given cartridge. Picking the highest BC bullet available in that given caliber usually meant it was also the heaviest of the given caliber selection.

This is evident in the emergence of the 6.5mm Creedmoor cartridge. 6.5mm Creedmoor has achieved widespread market adoption in recent years, bringing the advantages of the 6.5mm bullet to the mainstream, and prompted the development of many other 6.5mm / .264 caliber bullets.

In the 6.5mm Creedmoor cartridge, the most commonly used bullet is a 140gr variant, due in part to the Hornady 140gr A-Max 6.5mm Creedmoor factory ammunition (superseded by the Hornady 140gr ELD Match), but mainly due to the high BC. Other ~140gr bullets such as the Sierra Match King 6.5mm 142gr and the Berger 140gr Hybrid Target with high BCs are also quite popular in the 140gr family.

The 140gr/142gr (and most recently a 147gr Hornady ELD Match) bullet is about the heaviest available in the 6.5mm/.264″ family, and given that these have a higher BC than everything else in the same caliber, people tend to gravitate to the 140gr+ rounds.

If 140gr+ offers a higher BC, why bother with the lighter bullets in the same caliber (and of similar design) with a lower BC? This is where it gets interesting.

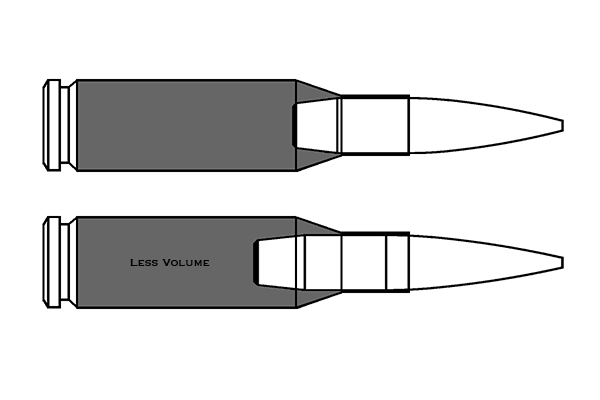

The heavier the bullet in a given cartridge (e.g. 6.5mm Creedmoor), the slower the muzzle velocity due to a combination of smaller case capacity for the powder (larger bullet can result in taking away space when it is seated) and pressure limitations (can only use so much powder to push the bullet).

With a lighter (shorter) bullet in that same cartridge, you can get more case capacity for the powder

The above diagram shows how a heavier (and inherently longer) bullet can result in less case capacity/volume for the powder, especially if the bullets are seated with an equal cartridge overall length (COL).

Generally, a 140gr bullet in 6.5mm Creedmoor is moving with a muzzle velocity of 2700fps (sometimes higher with custom handloads) out of a 24″ barrel. Given the fairly high BC in a 140gr bullet, performance in the wind is quite good compared to other short action cartridges. But trying to push any further can result in higher pressures with decreased case life or even dangerous conditions.

On the other hand, a 130gr bullet in 6.5mm Creedmoor is typically moving at around 2900fps (sometimes higher with custom handloads) out of a 24″ barrel. But typically, the 130gr 6.5mm bullet has a lower BC than a 140gr 6.5mm bullet, especially with the same or similar design (shape).

So higher ballistic coefficient is still going to be better for long range shooting, right? Well, it all depends and this is where the debate begins.

I have been a proponent of Berger Bullets ever since I started using the Berger Bullets 22cal 80gr VLD in the AR-15 for High Power Service Rifle competition (on the 600 yard line). So when I started working on loads with the 6.5mm Creedmoor, I developed for two specific Berger Bullets:

- Berger Bullets 6.5mm 140gr Hybrid Target

- Berger Bullets 6.5mm 130gr AR Hybrid OTM Tactical

Both of these bullets are Berger ‘Hybrid’ designs which are supposed to be very jump tolerant, and can be seated farther away from the lands of the rifling and still have good accuracy. This is important for platforms (rifles) where the operator needs to use rounds that can only be as long as the magazine length allows (e.g. 2.260″ for the AR-15).

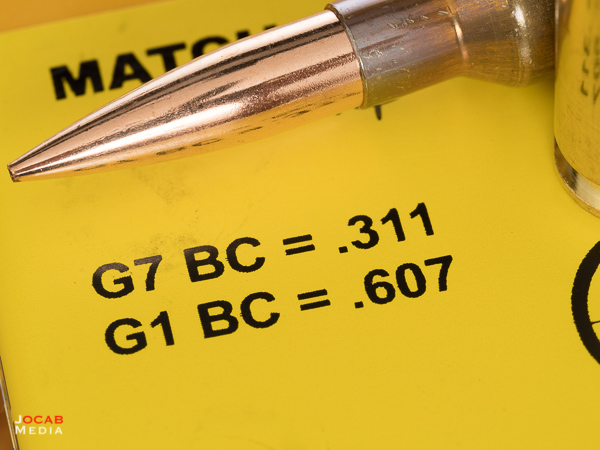

I first started off with the 140gr Hybrid Target because it had one of highest ballistic coefficient values advertised with a G7 BC of .311.

It is important to know that manufacturer ballistic coefficient values have historically been inaccurate and overstated. But in recent years, better testing procedures have allowed manufacturers to obtain a more accurate, real world BC value for their bullets. So assuming the manufacturer took the time to have the respective bullets tested in a quality lab environment, the advertised BC should be true. Berger Bullets is one such manufacturer that makes an effort to provide accurate ballistic coefficient values to the public.

I was able to achieve a good 6.5 Creedmoor load with the 140gr Hybrid Target that pushed it with a muzzle velocity of 2750fps. This velocity with the G7 BC of .311 yields a highly respectable trajectory when run through a ballistic calculator.

I then started testing out the the 130gr AR Hybrid OTM Tactical which has a comparatively lower G7 BC of .287.

I was able to easily push the 130gr AR Hybrid at 2900fps and could hit 2930fps without any severe pressure signs. The 2900fps muzzle velocity of the G7 BC of .287 also yields a respectable trajectory when through a ballistic calculator.

Note that while a lighter bullet will usually have less BC to a heavier weight bullet in the same caliber, the BC can still be high enough to be stable at long range, as long as it achieves the appropriate velocity as it exits the muzzle.

The primary reason why people emphasize high ballistic coefficient is to beat the wind: minimize the effect of wind on the bullets flight to the target.

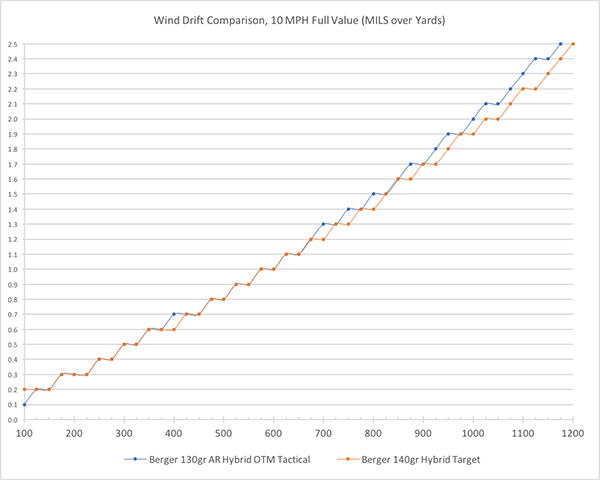

The above scatter line graph represents the values of windage correction in MIL for a 10mph full value (90 degree angle) wind from 100 yards to 1200 yards at 25 yard intervals where:

- Blue line represents Berger 130gr AR Hybrid starting at 2900fps muzzle velocity

- Orange line represents Berger 140gr Hybrid Target starting at 2750fps muzzle velocity

The conditions are the same for each bullet (3000ft altitude, 100 yard zero).

As you can observe in the above scatter chart, each bullet is affected a 10mph cross wind in the same manner until the 700 yard mark. At 700 yards, the affect of wind is more prevalent on the 130gr AR Hybrid, and you can see that it needs more windage correction than the 140gr Hybrid Target. At 1000 yards, there is clear separation of the scatter lines as the 140gr Hybrid Target evidently needs less windage correction for the same 10mph wind.

Obviously, if you were shooting at 800 yards and beyond in variable winds, you would desire the 140gr Hybrid Target moving at 2750fps over the 130gr AR Hybrid moving at 2900fps, simply because that bullet is able to resist the wind better at longer distances.

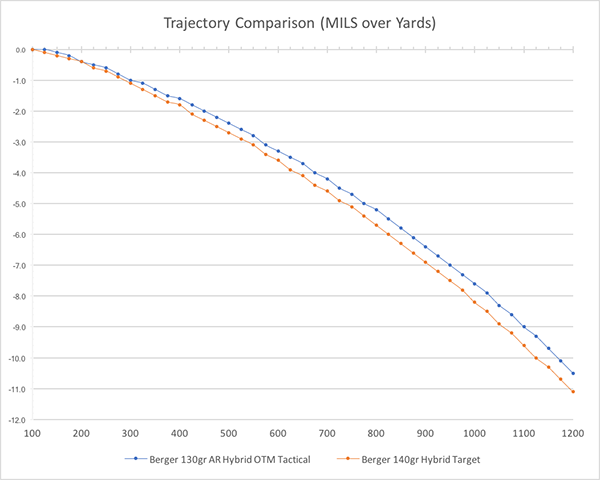

But when you compare the trajectories of the 130gr AR Hybrid OTM Tactical and the 140gr Hybrid Target, you will see the advantage switch.

The above scatter line graph represents the values drop of the bullet in MIL from 100 yards to 1200 yards at 25 yard intervals where:

- Blue line represents Berger 130gr AR Hybrid starting at 2900fps muzzle velocity

- Orange line represents Berger 140gr Hybrid Target starting at 2750fps muzzle velocity

The conditions are the same for each trajectory (3000ft altitude, 100 yard zero).

As you can see in the above chart, not only does the 130gr AR Hybrid drop less than the 140gr Hybrid Target, the rate of drop is actually less as well. This equates to what many often refer to as a ‘flat’ trajectory.

But why is the flat trajectory of the Berger 130gr AR Hybrid (2900fps MV) more advantageous than the Berger 140gr Hybrid Target (2750fps MV)? Does it matter when you know the distance of the target and you can simply adjust the elevation knob?

If you know for a fact that a given target is 1000 yards away (e.g. a known distance range), the no, there really is no advantage of a flatter trajectory. You would much rather have the Berger 140gr load for the higher BC and wind resistance.

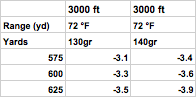

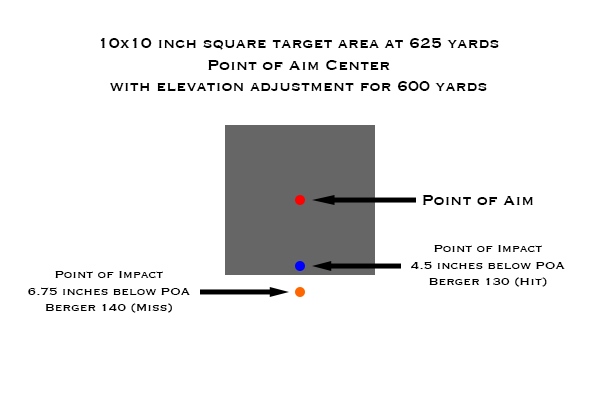

But let us say you are shooting on a unknown distance range or in a scenario where you are ‘unsure’ of the target distance? What happens if you misestimate the range of the target to be 600 yards when it is actually 625 yards?

If you were using the Berger 140gr Hybrid Target load, you would mis-dial 3.6 MIL up elevation for 600 yards, when the target is actually at 625 and needs 3.9 MIL up elevation, resulting in 0.3 MIL elevation difference.

Assuming you use the generalized conversion of 3.6 inches per 1 MIL at 100 yards, this equates to 22.5 inches per 1 MIL at 625 yards. Three-tenths (0.3) MIL equates to 6.75 inches at 625 yards.

This would mean you would shoot 6.75 inches low on the target at 625 yards if you misestimated the target distance as 600 yards.

On the other hand, if you were using the Berger 130gr AR Hybrid OTM Tactical load, you would mis-dial 3.3 MIL up elevation for 600 yards, when the target is actually at 625 yards and needs 3.5 MIL up elevation, resulting in 0.2 MIL elevation difference. The two-tenths (0.2) MIL difference equates to 4.5 inches at 625 yards.

This would mean you would shoot 4.5 inches low on the target at 625 yards if you mis-estimated the target distance as 600 yards.

A difference of 2.25 inches at 625 yards may not sound like a lot, but this could mean the difference between a hit and a miss, especially when you start to factor in variables such as effective target size, trajectory variances due to environmental conditions, and shooter hold error.

The above example illustrates a hypothetical miss on target with the described incorrect range estimation of a target as being 600 yards away when it is actually 625 yards away.

Of course, if this above scenario were with a 6×6 inch target, both rounds would have missed, so there will be situations where the flatter trajectory still is not ‘flat’ enough to save you for poor range estimation. Then of course, the rate of drop starts to equalize between the 130gr and 140gr bullet trajectories at around the 700 yard mark after the trajectory drop rates have deviated from one another, negating the flat trajectory advantage.

So do you pick the lighter and faster bullet over the heavier and slower bullet and sacrifice wind deflection at longer distances in order to gain the trajectory advantage at the short to mid-range distances?

That is the dilemma.

The argument for the heavier and slower bullet (with higher BC) is that the BC advantage helps you fight a factor you cannot control: wind. Wind and the way it behaves in a given environment is out of the shooter’s control. The shooter attempts to read it and translate it into a windage adjustment. Whereas a distance / ranging estimation is actually something the shooter has control of. The shooter could use a laser rangefinder and get the true distance to target and adjust the elevation accordingly.

The argument for the lighter and faster bullet is that there are times where you cannot use a laser rangefinder and must use other means to range the target. There are also times where the target could be moving towards or away from the shooter resulting in a variable distance condition. To counter the argument that the heavier and slower bullet with the higher BC is better in the wind, one could cite the comparative wind drift chart above for the 130gr and 140gr rounds and note that the difference in windage adjustment is negligible at short to mid-range, and only minor at long range.

There is no truly right choice when it comes to picking a lighter, faster round versus a heavier, slower round. It is up to the shooter to decide which fits the given environment and shooting style.

Where do I stand? I personally favor the lighter and faster round for the flatter trajectory and find the ‘disadvantage’ in wind drift at long range negligible, especially since it is still far better than what I get with the traditional .308 Winchester and 175gr BHTP.

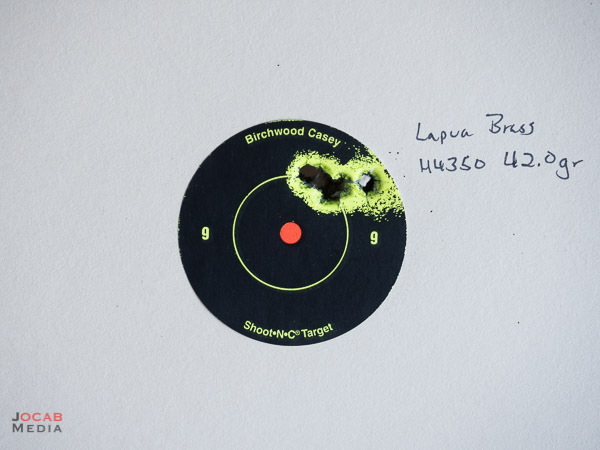

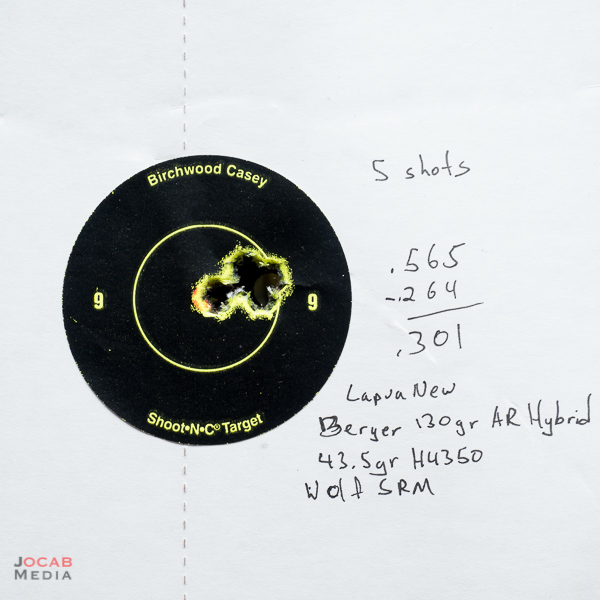

I am using the Berger Bullets 6.5mm 130gr AR Hybrid OTM Tactical as my primary load for my 6.5 Creedmoor rifle:

- Berger Bullets 6.5mm/.264″ 130gr AR Hybrid OTM Tactical

- 43.2gr Hodgdon H4350

- Lapua or Hornady brass

- CCI BR4 or Wolf SRM Primer

- Muzzle Velocity: ~2900 fps

For more information on the Berger Bullets 6.5mm 130gr AR Hybrid OTM Tactical, read the Berger Bullets press release for this bullet when it was released in 2015.

Bryan

This was a great article, and exactly the consideration I was trying to make in my 6.5. I think I will try the 130 OTMs.

Bruce Bracken

Good information. Wondering if the higher MV of a lighter bullet is already considered in its stated BC?

Jonathan Ocab

The basic definition of BC is the ability for the bullet to overcome air resistance in flight. However, it can also be defined even more simpler as the ability for the bullet to maintain velocity. While the G1 ballistic coefficient is directly related to velocity, what range of MV’s to come up with which G1 BC value to put on a box is probably set generically at the 2000-2200 fps range.